Since its 2013 release, Martin Lee’s Smoke Signals has received scores of praise in and out of the cannabis community for its portrayal of the movement, the people and its impact on the culture of the 1960s and beyond. Through thorough research, Lee details the history of the cannabis movement from London to the Bay Area to the East Village. Notable names of the movement are profiled, including Allen Ginsberg and Ed Sanders who, among numerous acts, took part in protests and rallies in support of cannabis and the resistors who were detained along the way. Often, they were included in the detention as well. Much of the focus on New York’s underground cannabis saga focuses on the East Village – a hotbed for underground counterculture communities and information at the time. Through bookshops, coffeehouses and newsletters, the cannabis community grew unified and stayed informed of what was happening during these tumultuous times.

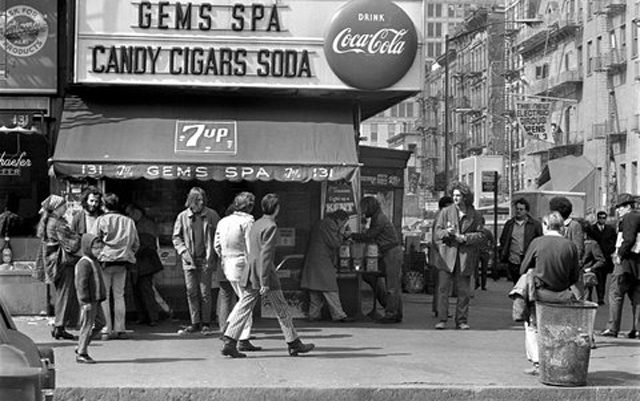

The East Village was often regarded for its diversity along each street. People who frequented the area during the 1960s often recall its openness and inclusion. Some even claimed it was on par or beyond famed locations, such as Haight-Ashbury in San Francisco. On these streets, New Yorkers and tourists gained cultural immersion that they could not find elsewhere.

Numerous bookstores, coffee shops and underground meeting places served as gathering grounds for the beatnik movement and its pro-cannabis agenda. From establishments like Ed Sanders’ Peace Eye Bookstore on 10th Street would Ginsberg and others convene to discuss ideas and buy books. Most topics tackled the state of the planet, with cannabis often factoring in the topic to some degree. With Ed Sanders, a devout believer and partaker in the “total assault” on mainstream culture, cannabis served as the prime weapon in the culture war against the misinformation the led cannabis to become demonized. It was a common sight to see posters flying off the press at Peace Eye.

9 Bleecker Street was another destination for the counterculturalists of the day. The three-story building driven by the ideals of the Youth International Party, or Yippies, brought together beatniks and other minds to think far outside the boxes of politics and the mainstream. Social justice and progress were always on the menu and continued to be for 40 years until it was foreclosed on in 2014. A former occupant of the building in the mid to late ’70s told The New York Times that the landmark for free thinking had “survived all these years when similar gathering spots around the country went under.”

Another prominent name in the movement wasn’t a destination but a publication. The Underground Press Syndicate, also later known as the Alternative Press Syndicate, was founded in 1966 by Tom Forcade, who would later open High Times Magazine. The UPS and other underground publications distributed cultural news that the mainstream wouldn’t touch. With their bias on clear display, there was no hiding their goals. These newsletters and publications relied on ground reporting from the likes of the Liberation News Service (LNS), who acted as the counterculture movement’s AP wire. Together, they furthered the counterculture movement, which would go on to permanently shift thinking in America and beyond.

That shifting, however, also happened in the East Village. While shades of the counterculture movement can still be found, almost all of the past has faded away. Today, the East Village is home to a neighborhood that is constantly in development. Even homes on the tiniest sidestreets can be found under construction. The arts community has been priced out to give way to boutiques and the city’s more affluent individuals. So much so that even one of the counterculture’s longest-running publications, The Village Voice, ended its print publication in 2017 and ceased operations not too long after.

That said, the spirit of the 1960s still exists in those that experienced what New York, and the East Village in particular, was like first-hand. Louis Santiago told The Marijuana Times that, “The ’60s was a blast.” After public school exposed the young adult into drugs and the flawed school system, Santiago eventually found himself working his way up the marijuana delivery ladder. That included making deliveries to East Village coffee and bookshops.

Through the years, Santiago would deliver to the Village, Midtown and all over New York City, eventually moving into larger vehicles and his own independent trucking operation by 19. Santiago has fond memories of the East Village, Washington Square Park in particular, where cannabis culture is still a prominent component in the park. However, Santiago recognized that the spirit of the East Village transcended the community. “People that smoked pot smoke pot.” He added, that from Sheepshead Bay to Midtown to Staten Island, “Someone was looking to get some pot…the city was a big place.” Today, he is working on his memoir from his home in New Jersey about his experience with cannabis and the law.

Craig Zaffe shared similar feelings as Santiago when it came to cannabis culture. While he spent more time in other parts of New York City such as Harlem, he noted that the culture permeated through those enamored with the movement. “[The underground experience] was an awakening to that whole culture.” Zaffe added, “You saw your first tattoo, your first ponytail, the colorful clothing, the whole essence of the cannabis culture – we wanted to be a part of it.”

Today, Zaffe explains that he is the only one of his friends still active in cannabis while they stay at home. Instead, he operates a CBD business, Your CBD Oils, just outside of the city. To grow his business, Zaffe is active in networking events – a stark contrast to the days of the ‘60s. He is also present at underground cannabis expos and parties. While different in tone than the meetups in the East Village, Harlem or other parts of New York City, these hush-hush events continue to carry shades of the past’s ethos and procedures.

The rising property prices and numerous other price hikes forced the East Village’s counterculture history out much as gentrification has done to generations of people of color and low income status. Today, most of the books, publications and other relics of the era can be found in museums and showrooms. Additionally, with the period carrying such immense value to the history of our culture, it has been preserved rather well. While not entirely legal, torrents and websites carry troves of documents that can be viewed as PDFs and scanned images. In more by the book measures, and potentially square by beatnik standards, there are plenty of excellent online databases that come at little to no charge. One such free option is Jacksonville State University’s extensive collection of the Underground Press Syndicate and other excellent finds.

While the evolution of the East Village may not embody the spirit of the movement, the counterculture has long since transcended physical space and continues to live on. Thanks to digital and physical preservation, its impact won’t be lost to history anytime soon.

i used to live and work at 9 bleecker street-the site of the yippie museum…

if it wasnt for the space, the existence of the yipstertimes/overthrow may not have happened…also it was my base of operations when it came to me pieing right wing pigs….well the corporatocracy ripped us off but the good fight goes on…see my site http://www.pieman.info